Scientists Just Built a Working Computer Out of Mushrooms. I know what you’re thinking. Mushroom computers sound like something out of a sci-fi novel where mycelium networks take over the world. But it’s real. Researchers at Ohio State University just published work in PLOS ONE that explains how they’ve done it. And it’s fascinating.

The Breakthrough

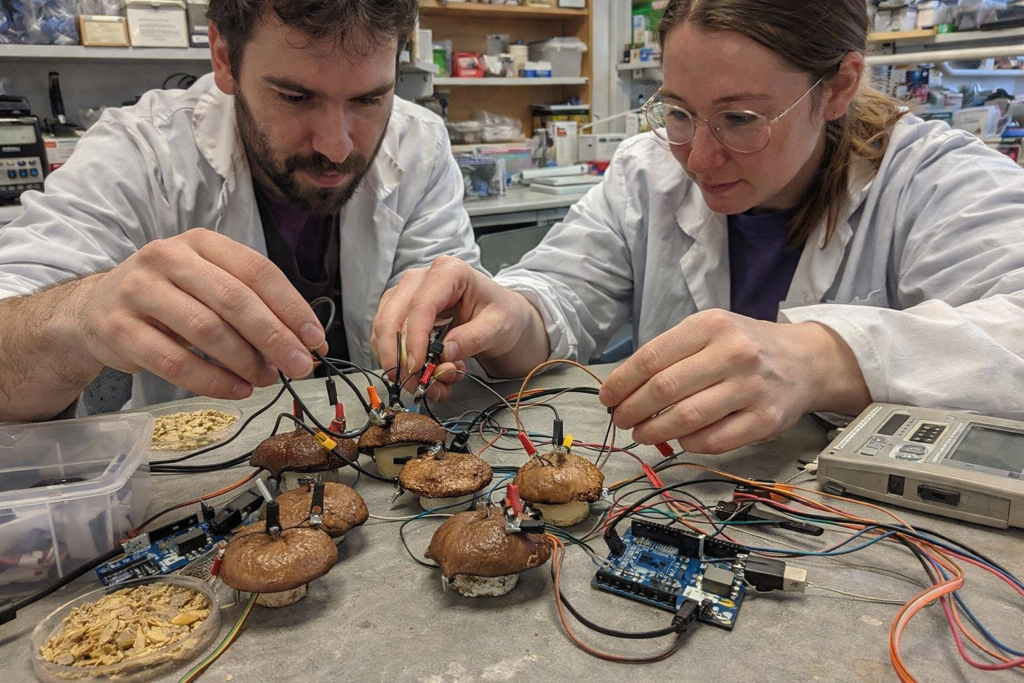

John LaRocco and his team did something beautifully simple: they grew shiitake mushrooms (yes, the ones you put in your stir-fry) in petri dishes, dehydrated them, and turned them into functional computer memory.

These fungal memristors (memory resistors) can switch between electrical states up to 5,850 times per second with 90% accuracy. They’re essentially doing what silicon chips do, but they’re made of mushrooms.

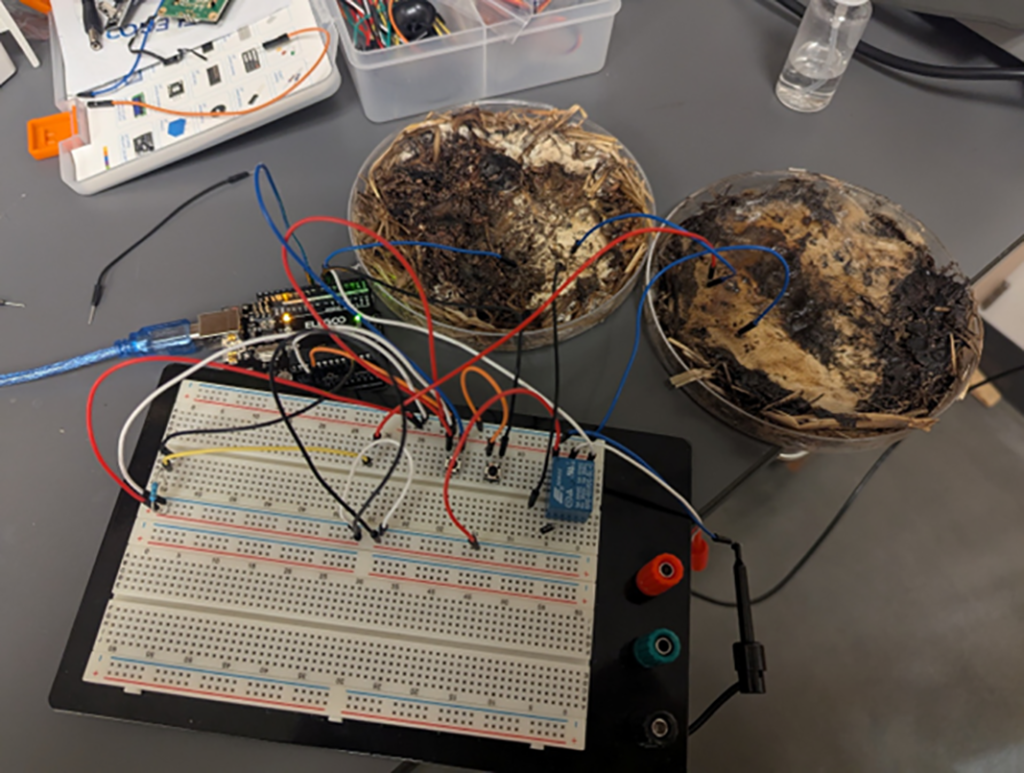

The researchers grew these in standard petri dishes with farro seed, wheat germ, and hay. LaRocco literally said you could start exploring this with “a compost heap and some homemade electronics.” This is garage biology meets computing.

Why This Matters

We’re always talking about how modern food systems are so damaging to human health. Well, turns out our computing systems have the same problem. They’re catastrophic at a planetary level. Data centres consume massive amounts of energy, require rare earth minerals mined in destructive ways, and generate mountains of e-waste.

Fungal computers flip this entirely. They’re:

- Biodegradable (literally grows and composts)

- Low energy (they work like brains, only using power when actively processing)

- Made from organic materials anyone can grow

- Radiation resistant (more on that in a sec)

Where it gets really interesting for me is the potential for decentralisation. Right now, computing is hyper-centralised – massive server farms, specialised foundries in a handful of countries, supply chains dependent on rare materials and geopolitical stability.

But if you can grow a memristor in your backyard? That fundamentally changes the equation. LaRocco mentions applications ranging from “as small as a compost heap” to “a culturing factory.” This is democratised technology, with the means of production becoming accessible to communities, not just corporations.

Radiation Resistance

Shiitake mushrooms are radiation resistant. The paper discusses how fungi can adapt to radiation exposure through compounds like lentinan and increased melanin production. There’s even research showing fungi thriving in space conditions. This is pretty important.

It means fungal computers could work in places where conventional electronics fail, like on spacecraft, high-radiation environments, and maybe even as backup systems that survive catastrophic events. Fungi are arguably the most resilient organisms on earth. Meaning we could essentially encode fungal resilience into our technology, making ourselves more resilient in the process.

The Vision

The world is at a point where we realize we need to switch from extraction to regeneration if we are to continue to thrive on this planet. And what really strikes me about this innovation is how it embodies regenerative thinking.

Instead of extracting rare minerals from the earth, processing them in energy-intensive foundries, and creating toxic waste, we’re growing our technology. The mushroom does the work. It builds its own network of mycelial threads (hyphae) that naturally form the conductive pathways needed for computing.

And when you’re done, it composts. The whole lifecycle is circular.

This connects to something we see in metabolic health too. The body has inherent wisdom. Give it the right conditions, and it self-organises toward health. Same with fungi. Give them the right substrate and electrical stimulation, and they self-organise into functional computing elements.

The (Simplified) Science

For the nerds out there, this is how the science works. Memristors are electronic components that “remember” previous electrical signals. They’re key to neuromorphic computing – aka computers that work more like brains, with memory and processing integrated instead of separated.

The team grew shiitake cultures, dehydrated them for stability, then connected electrodes and ran various electrical tests. At certain frequencies (especially around 10 Hz with proper voltage), the mushrooms displayed the characteristic “pinched hysteresis loop” that signals memristive behaviour. Basically, they could store and switch between electrical states reliably.

For volatile memory testing (like RAM), they built a simple circuit with two mushroom memristors and an Arduino. The system could write and read memory states up to 5,850 times per second. Performance dropped at higher frequencies, but – and this is crucial – they found you could compensate by adding more mushrooms to the circuit. Just like brains add more neurons for complex tasks.

The Limitations

In reality, this isn’t replacing your laptop tomorrow. The researchers are honest about the limitations:

- Current devices are bulky (need serious miniaturisation)

- Study was short-term (less than two months)

- Growth conditions create variable results

- We need better cultivation and preservation techniques

But these are engineering challenges, not fundamental barriers. And unlike semiconductors, the barrier to entry for experimentation is incredibly low.

What This Opens Up

I keep thinking about the implications:

For sustainability: Computing that doesn’t require mining, doesn’t generate toxic waste, and uses minimal energy. The whole system is regenerative by default.

For accessibility: Communities could grow their own computing substrates. Indigenous knowledge about mushroom cultivation becomes relevant to high-tech applications. The Global South doesn’t need semiconductor fabs to participate in advanced computing.

For resilience: Biological systems that can work in extreme conditions, self-repair, and adapt. Computing that survives what would kill conventional electronics.

For innovation: When the means of production are democratised, weird and wonderful applications emerge. Edge computing in remote areas. Wearable bioelectronics. Aerospace applications. Things we haven’t imagined yet.

The Bigger Pattern

This research gives up an insight into a potential future.

We’ve spent the industrial age treating nature as something to dominate and extract from. But the most sophisticated technologies on Earth are biological. They’re self-assembling, self-repairing, adaptive, efficient, and cyclical. They run on sunlight and return to soil.

What if computing looked more like that?

LaRocco’s team is demonstrating a different relationship between technology and biology. One where we work with living systems instead of trying to replace them with dead materials and brute force energy.

The Future Might Be Fungal

The paper ends with this: “The future of computing could be fungal.”

I think they might be right. Mushroom computers won’t replace everything (at least not anytime soon). But they represent a paradigm shift. They show us that high-tech doesn’t have to mean high-impact. That accessibility and sophistication aren’t opposites. That regeneration and innovation can be coupled.

Technology is moving fast these days. Imagine telling someone a few decades ago that one day we’d be growing our computers from fungi. They’d think you were high.

But here we are. The mushrooms are computing. The future is here. And who knows what’s coming next?

The research: “Sustainable memristors from shiitake mycelium for high-frequency bioelectronics” by LaRocco et al., published October 10, 2025, in PLOS ONE. Supported by Honda Research Institute.