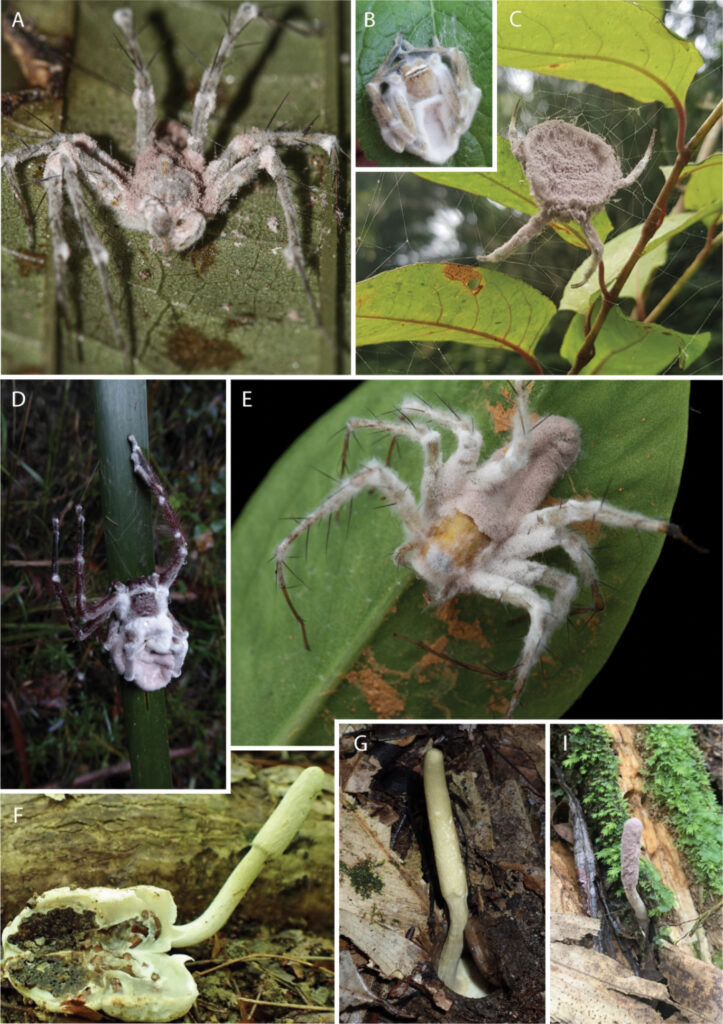

Picture this. You’re a trapdoor spider, buried safely in your burrow beneath the leaf litter of Brazil’s Atlantic rainforest. You’ve survived this long by staying hidden, waiting to ambush prey. Then one day, microscopic spores find their way in. The fungus takes hold. Your body becomes a cotton-white tomb. And from your corpse, a 2-centimeter fruiting body punches through your trapdoor, releasing spores into the air above.

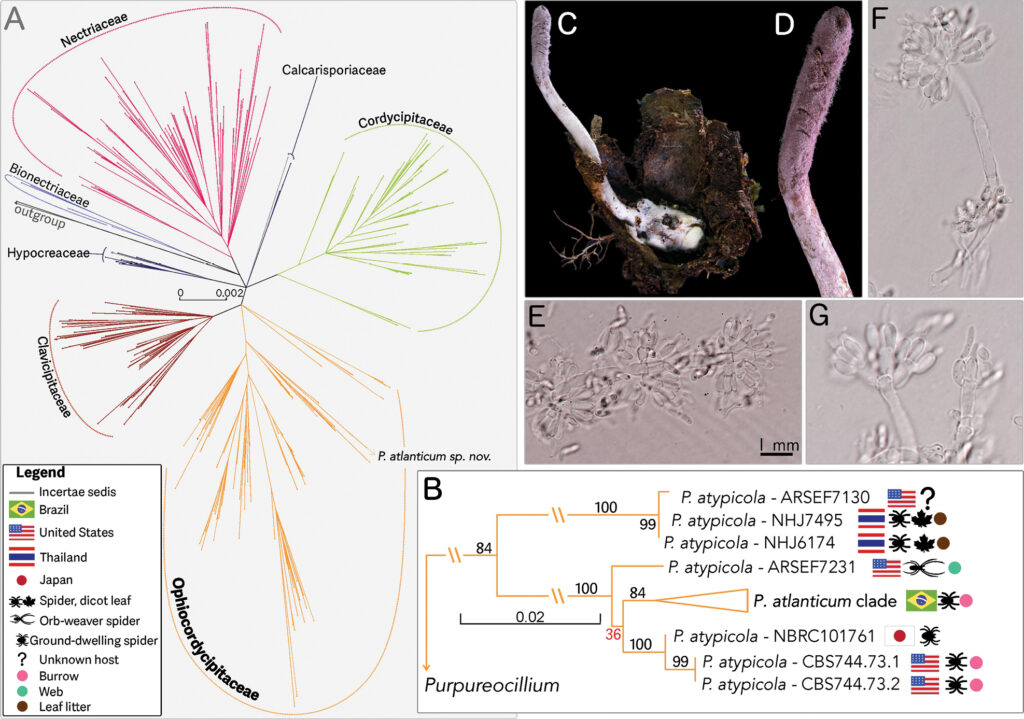

Welcome to the world of Purpureocillium atlanticum, one of 65 new fungi species described by scientists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and their collaborators in 2025. It’s a member of what researchers call “zombie fungi” – organisms that parasitise other creatures to complete their life cycle. This particular specimen has chosen trapdoor spiders as its host.

The Hidden Kingdom

The majority of the fungi kingdom is a mystery. Scientists estimate there could be 2-3 million species of fungi on Earth. We’ve named about 200,000 of them. That means we’ve described roughly 10% of fungal diversity.

Dr. Irina Druzhinina, who leads fungal diversity research at Kew, calls it “one of science’s most exhilarating frontiers of discovery.” She’s not exaggerating. Every year, taxonomists describe around 2,500 new plant species and similar numbers of new fungi. The Atlantic rainforest alone (where this spider-killing fungus was found) continues to yield discoveries that reshape our understanding of ecosystem relationships.

In Field Analysis

What makes this discovery particularly fascinating is how it was made. The research team, led by Dr. João Araújo from the University of Copenhagen and Kew’s Professor Alex Antonelli, used Oxford Nanopore sequencing (aka portable DNA sequencing technology) right there in the rainforest. No need to ship samples back to distant labs and wait months for results.

This “taxogenomic” approach (combining classical taxonomy with genomic analysis) let them decode the fungus’s complete genetic blueprint on-site and identify its associated microbiome (the community of bacteria and other fungi living alongside it). Faster identification means faster understanding of ecological relationships, which means more effective conservation decisions.

Their genomic work revealed that P. atlanticum appears to belong to a complex of cryptic species that infect different spider hosts across the globe. What looks like one organism might actually be several closely related species, each adapted to specific ecological niches and hosts.

Delicate Balance of Decay

From a metabolic perspective, these entomopathogenic fungi are doing something remarkable. They’re essentially hijacking the spider’s biology, breaking down its tissues to fuel their own growth, then timing their reproductive phase to maximise spore dispersal. The fungus has evolved to recognise when the host is completely colonised, produce a fruiting structure that navigates through the burrow’s architecture, and emerge into open air at exactly the right moment.

This is a display of precision metabolic engineering shaped by millions of years of co-evolution. The fungus must balance aggressive tissue colonisation with maintaining structural integrity long enough for successful reproduction. Too fast and the host collapses before spores can disperse. Too slow and competing organisms might colonise first.

Gruesome, but fascinating.

Extinction Risk

There is some bad news, though. Araújo notes that increasingly, the species taxonomists describe as “new to science” are already threatened with extinction, or even appear extinct at the point of publication. The Atlantic rainforest, where this fungus was discovered, has been reduced to just 12% of its original extent.

Think about the implications. In natural systems, every organism plays multiple roles we don’t yet understand. These zombie fungi might regulate spider populations, influence nutrient cycling, interact with plant root systems, or produce compounds with pharmaceutical potential. We’re dismantling these networks before we can even map them.

Fungi are essential to ecosystem health, forming networks that connect plants, cycling nutrients, and structuring soil communities. So the work to discover and describe them is not just about finding cool new species. Understanding them helps us decode the infrastructure that makes terrestrial life possible.

The Work Ahead

Kew’s scientists named 125 plants and 65 fungi in the past year alone. It’s impressive work, but set against 2-3 million unknown fungal species, it underscores the scale of the challenge. As Dr. Druzhinina puts it: “The challenge is immense but so is the wonder and privilege of uncovering new branches on the tree of life.”

The spider-killing fungus from Brazil is a gruesome curiosity. But it’s also a reminder that even in well-studied ecosystems, fundamental discoveries await. Every new species adds resolution to our understanding of how life actually works.

We’re racing to describe biodiversity while simultaneously watching it disappear. The question isn’t what we’ll find next. The question is whether we’ll preserve the conditions that allow them to exist long enough to tell us their secrets.

You can read the full study on Purpureocillium atlanticum in the journal IMA Fungus here, and explore Kew’s complete list of top 10 species for 2025 on their website here.