The mushroom that carpets British pastures every autumn carries one of history’s strangest stories—a tale that winds from ancient Rome through political revolutions, arrives at a poetry lecture in 1960s Oxford, and ends up in cutting-edge psychiatric trials today.

A Symbol Born in Chains

The name ‘liberty cap’ has nothing to do with hippies or counterculture. It goes back to ancient Rome, where freed slaves were given a conical felt hat called a pileus. It meant you were free, but signified to everyone that you’d been enslaved. Freedom, yes, but with an asterisk.

Then in 44 BC, after Julius Caesar’s assassination, Marcus Junius Brutus did something clever. He stamped that same cap onto coins, turning it into propaganda that proclaimed Rome was now “free” from tyranny. The liberty cap became a symbol of political revolution, resurfacing centuries later during the American and French revolutions.

Fast forward to 1803, and the English poet James Woodhouse compared mushrooms to “Freedom’s cap” – a metaphor picked up by heavyweights like Robert Southey and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. As mycology became a proper science in the 19th century, the name stuck to Psilocybe semilanceata, the little pointed mushroom that dots British fields.

First formally described in 1838 by Elias Magnus Fries, the mushroom remained a botanical footnote for over a century. Nobody had any idea what it could do.

From Oxford To Infinity

The British magic mushroom story really begins in a very English way: with an Oxford poetry lecture.

It’s 1962. Robert Graves – war veteran, celebrated poet, and intellectual force of nature – stands before an audience and calls the mushroom “divine ambrosia.” He’d tried psilocybin pills after his friend, ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson (perhaps the first white man to eat magic mushrooms), returned from Mexico with wild tales of sacred mushroom ceremonies. Graves reported experiencing “utter peace and profound wisdom” in what he described as “blue-green grottoes of the sea.”

Finally, in 1969, scientists confirmed that Britain’s humble liberty cap contained the same compound Hofmann had isolated in 1958: psilocybin.

Graves, with all his classical credibility, had essentially given permission for “bold experimenters” to try Britain’s native species for themselves. What started as high-minded academic curiosity became a full-blown cultural phenomenon. Within years, psychedelics were reshaping British music, fashion, art, and consciousness itself.

The Psychedelic Explosion

After Robert Graves gave his blessing in 1962, the liberty cap didn’t just influence British counterculture, it detonated it.

Within a few years, British youth were tramping through muddy fields in the Lake District, Sussex Downs and Scottish Highlands, filling bags with their own homegrown sacrament. The mushroom season became a pilgrimage, an annual ritual that turned ordinary pastures into outdoor pharmacies.

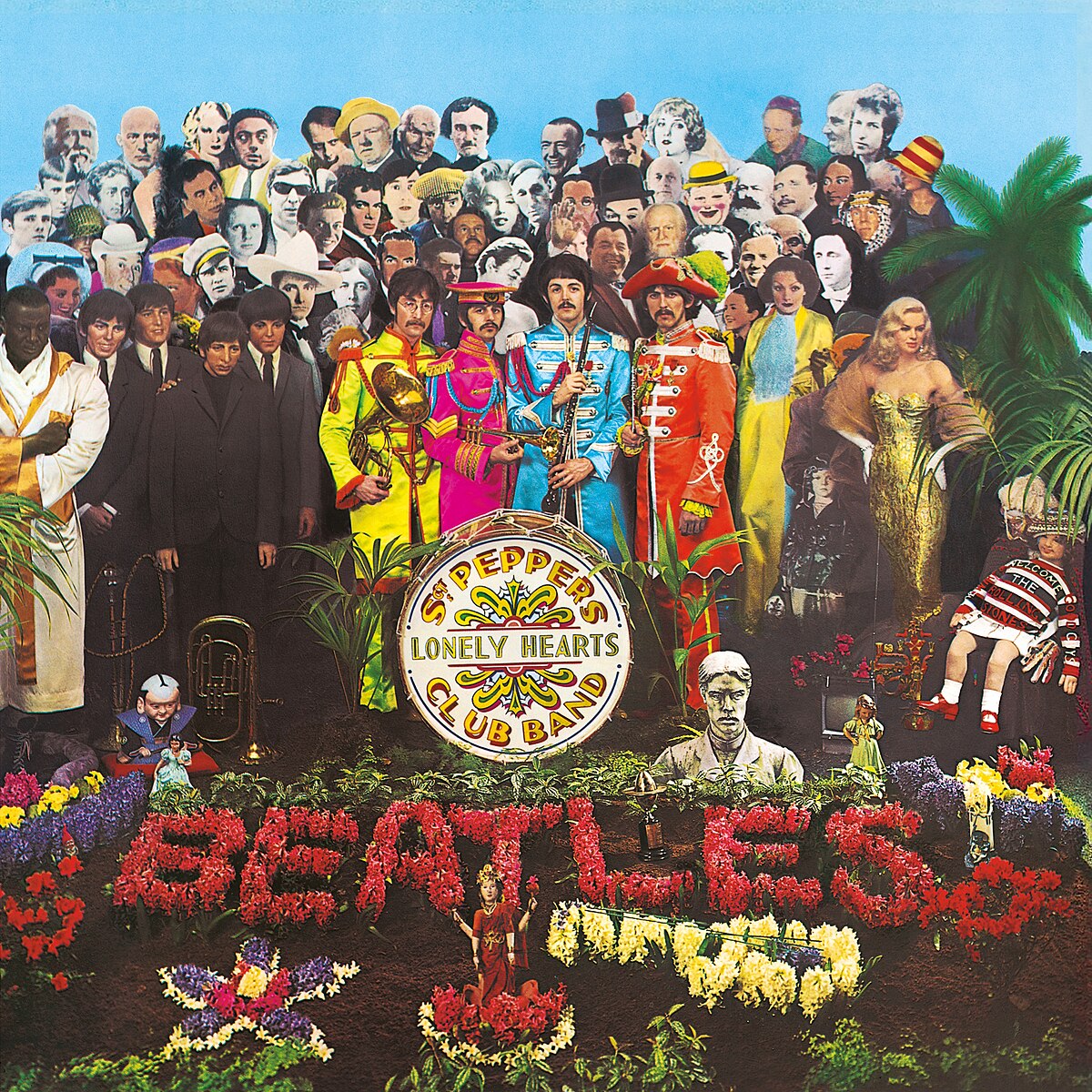

You can hear the liberty cap’s influence bleeding through British music from the mid-60s onward. The Beatles returned from their psychedelic experiments with Revolver and Sgt. Pepper’s, but it wasn’t just exotic trips to India or Californian acid that shaped British psychedelia. It was mushrooms sprouting in their own backyard.

Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett, already eccentric, dove deep into psychedelics during Cambridge’s folk scene. The result was The Piper at the Gates of Dawn—a kaleidoscopic masterpiece that sounds. The Incredible String Band wove mushroom-inspired mysticism into Celtic folk traditions. Donovan sang openly about getting “high” on a mountainside. Even the Stones got in on it, with their psychedelic period coinciding perfectly with Britain’s mushroom awakening.

Underground clubs in London’s Soho and Manchester’s Twisted Wheel became laboratories for a new sound. British acid rock, folk rock, and eventually prog rock all carried traces of the liberty cap experience: the dissolution of boundaries, the sense of ancient connection, the feeling that consciousness itself was expandable.

The same influence could be seen and felt in British psychedelic art from the late 60s and early 70s. Artists like Martin Sharp and the designers behind Oz Magazine created work that felt simultaneously ancient and futuristic. Many album covers, concert posters, and underground comics from this era depict psychedelic visions.

Fashion followed suit. The boutiques along King’s Road became temples to consciousness expansion, where clothes weren’t just garments but statements about altered perception. Geometric patterns, impossible colours, flowing fabrics, all trying to capture the feeling of boundaries dissolving.

A Homegrown Revolution

What made the liberty cap’s influence unique was that it was accessible. You didn’t need connections to underground chemists or smugglers. You just needed to know which fields to check in September, what the mushroom looked like, and enough courage to eat it.

This democratisation meant the psychedelic experience spread beyond London’s elite circles into universities, art colleges, and provincial towns across Britain. A farm worker in Wales could access the same consciousness-expanding experience as a Chelsea artist. The liberty cap was the great equaliser.

It created a shared language, a common reference point. When British musicians, artists, and writers talked about “expansion,” “the infinite,” or “the cosmic,” they were describing direct experiences that their audience knew.

The Hangover and the Revival

By the mid-70s, the initial explosion had settled into something more complicated. The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 had made psilocybin illegal, though enforcement was patchy and fresh mushrooms remained in a legal gray area until 2005. The utopian promises of the psychedelic revolution hadn’t materialised quite as hoped.

But the cultural influence didn’t disappear. It went underground and mutated. The rave scene of the late 80s and 90s, Britpop’s fascination with expanded consciousness, the current renaissance in psychedelic therapy, all of it traces back to those early experiments with Britain’s native magic mushroom.

Today’s psychedelic revival isn’t just about clinical trials and medical legitimacy. It’s about reclaiming a cultural heritage that was interrupted but never destroyed. The liberty cap influenced a generation of British artists, musicians, and thinkers who created work that still resonates today. And as legal restrictions slowly crumble, that influence is blooming again.

Like the underground mycelium that connects transient mushrooms overground, the counterculture didn’t die. It just went to seed, waiting for conditions to ripen again.

Counterculture to Clinical Trials

The irony is perfect. A mushroom named after freedom could get you locked up for years.

But something is shifting. Mainstream media and health officials are now asking a question that would’ve been unthinkable a decade ago: Should doctors prescribe magic mushrooms?

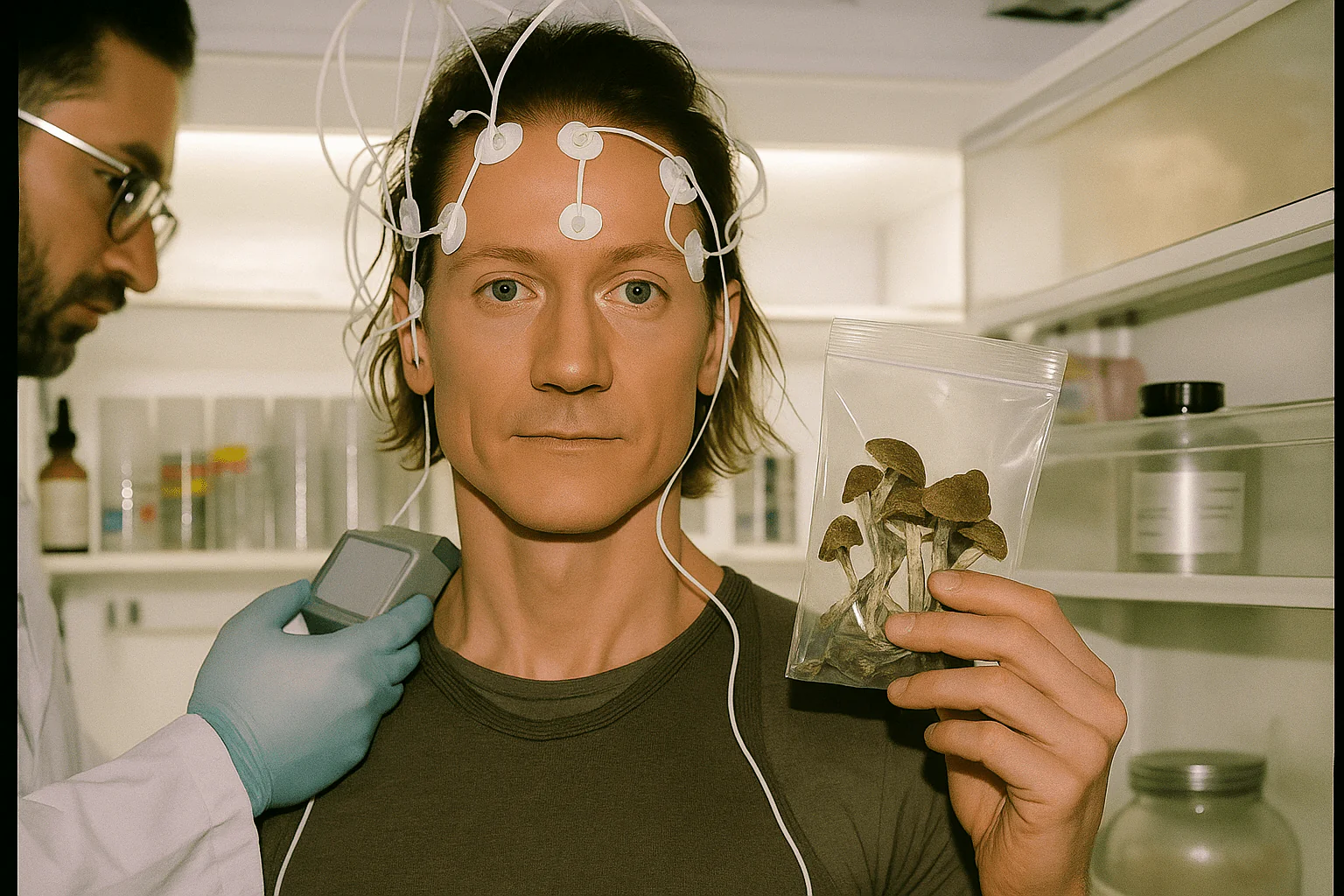

The evidence is stacking up. Since 2022, over 20 clinical trials have tested psychedelic medicines for depression, PTSD, addiction, OCD, and trauma. Many show huge promise. Some have mixed results. Only a few have found no benefit at all.

Prof Oliver Howes, chair of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Psychopharmacology Committee, is cautiously optimistic. “One of the key messages is that this is something we desperately need—more treatments and better treatments for mental health disorders,” he says. “These treatments are really interesting because they’ve shown promise in these small-scale studies and have the potential to work quicker.”

The UK’s medicines regulator is waiting on results from Compass Pathways (one of the largest psilocybin trials yet) expected later this year. The government has backed plans to ease licensing for approved clinical trials, with pilot projects underway. But doctors like Howes say change is painfully slow. “There’s still a lot of red tape holding things up.”

Nature Doesn’t Need Permission

Psilocybin is a Class A drug, but nature doesn’t care about human laws. Every September until the first frost, liberty caps bloom abundantly across UK pastures. Foraging has never been more popular.

Beyond legitimate medicine, many people see psychedelics as tools for spiritual growth and consciousness expansion – exactly what Graves was talking about sixty years ago. The liberty cap is living up to its name, offering a kind of personal freedom that can’t be restricted by governments.

From Roman slaves to revolutionary coins, from Romantic poetry and pop culture to psychiatric breakthroughs, this little mushroom has always been entangled with questions of freedom, consciousness, and what it means to be human. As we stand on the edge of psychedelic medicine becoming legal reality, the liberty cap’s story feels less like an ending and more like the beginning of something larger.

The symbol that marked freedom with an asterisk might finally deliver on its ancient promise.